4.4 3D Printing

4.4.3 Case Study: The Nefertiti Bust

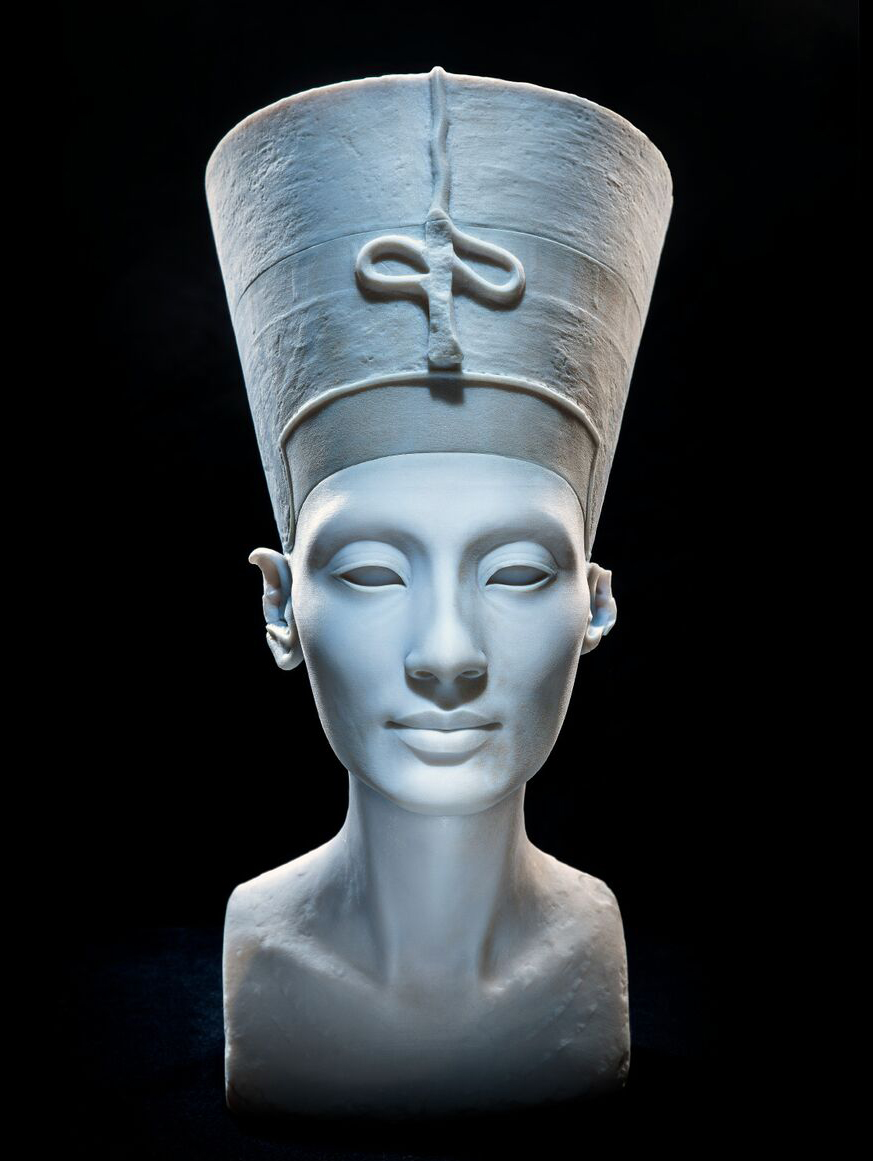

![]() Case Study: The Other Nefertiti

Case Study: The Other Nefertiti

|

|

The Other Nefertiti, 3D Print, Artistic Intervention by Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles. Click image to enlarge. https://theinfluencers.org/en/nora-al-badri-nikolai-nelles |

Since the public display of the bust in Germany, in 1923, Egypt has repeatedly asked for its repatriation. However, Germany has denied all such requests, even despite the threats from Egypt to ban the exhibitions of Egyptial artefacts in Germany. Among the various controversies that the bust has sparked is the one that claims that it is fake, either created by Borchardt to test ancient pigments or crafted by Hitler's orders as the original was lost in WWII. However, a computed tomography scanning of the bust in 2009 (Huppertz et al.) proved its genuineness, indicating differences between the inner and outer face of the bust, including the angles of the eyelids, creases around the corners of the mouth, and a bump on the ridge of the nose. CT scanning also revealed the soft spots of the bust indicating implications for its conservation.

|

Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles posing next to the Other Nefertiti. Aksioma - Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana, 2017. Photo: Jure Goršič/Aksioma. https://aksioma.org/the.other.nefertiti/ |

With the data leak as a part of this counter narrative we want to activate the artefact, to inspire a critical re-assessment of today’s conditions and to overcome the colonial notion of possession in Germany.

In the video below you can see the two artists scanning the bust using a Kinect sensor strapped to Al-Badri's torso, under her scarf and coat. According to the video, the artist walks around the exhibit, uncovering from time to time the kinect to scan the bust. During this time, Nelles is taking the video to show the scanning process. Many 3D and computer graphics specialists have commented on the Other Nefertiti by taking into account the high quality 3D model and the scanning process (Docherty 2016). Some of their observations point towards a hoax, since it does not seem possible to produce such a high quality scan using a kinect sensor and under these conditions. One of the most important concerns is about the fact that the bust is displayed behind glass. In most cases the glass will reflect light in different directions, while other visitors' reflections on it would create digital noise that couldn't be easily cleaned. Also, in order to produce an accurate 3D model, the whole object needs to be sufficiently scanned. Based on the position of the kinect sensor, the upper part of the bust was not in the field of view and therefore the amount of detail produced cannot be justified.

|

The Nefertiti Hack, video capture of the scanning process of the Other Nefertiti |

To these allegations the artists responded:

Maybe it was a server hack, a copy scan, an inside job, the cleaner, a hoax. It can be all of this, it can be everything...The whole question about originality and authenticity is the same in data as well as in artifacts, and as well in our effort. And, of course, that is our point...museums are telling fictional stories, their stories, just because they control the artifacts and the way of representation.

|

|

Artistic interventions and remixes of the Nefertiti 3D model. GIF produced based on the presentation by Al-Badri and Nelles at Influencers 2017. |

Accoridng to Al-Badri:

The head of Nefertiti represents all the other millions of stolen and looted artifacts all over the world currently happening, for example, in Syria, Iraq, and in Egypt…Archaeological artifacts as a cultural memory originate for the most part from the Global South; however, a vast number of important objects can be found in Western museums and private collections. We should face the fact that the colonial structures continue to exist today and still produce their inherent symbolic struggles.

The (3D) digitisation of heritage artefatcs brings to the fore questions in relation to ownership, provenance, and authenticity. Who owns the digital data? Is it the institutions that own the original artefacts or do notions of ownership collapse in the digital realm? Are the digital objects and their remixes less authentic in comparison to the original? Do they retain the aura of the original or do they generate a new aura as the result of the different types and levels of engagement with the public? These are all questions that are difficult to be answered but it is useful to reflect upon those, especially in cases where technology mediates the physical and generates new relationships and contexts.

Copyright in particular is still a grey area when it comes to 3D technologies. In a recent whitepaper, Weinberg (2016) argues that there is a difference between representational and expressive 3D scans. In the first case, the 3D model is an exact copy of the original (as much as possible given the capabilities of the technology), and the person who is producing it, only intends to create an accurate digital representation of the original. On the other hand, expressive scans are used to produce another work of art based on the original, which may have some resemblance to it but it is not its exact representation. Therefore, the scan is the result of a creative approach that involves much more than the technology used in the capturing process. This may mean that in the case of representational scans, the copyright may be retained by the owner of the original, while in the case of expressive scans, copyright of the digital may stay with the person/team who created the digital object. Cronin (2016) also questions the ethical dimension of 'hyperownership', i.e. when the rightful owners of an artefact that is part of the public domain may decide to exert their rights, e.g. by maintaining control over copying or use of copies. This will ultimately bring economic benefits (while protecting the artefacts), however, the question that we should ask here is: is it ethical to do so? Should the distribution of public domain artefacts be allowed or even encouraged or shall they remain part of cultural and political hegemonies and authorised heritage discources?

The underlying politics that such technological mediations bear should also not be underestimated. In the above case study it becomes obvious that the two artists had a political motive but also their intervention resulted discussions on the politics of heritage, issues of reproduction, and ownership, and the role of 3D technologies in the mediation of the past. In the exercise below, you are asked to work on a similar case, the 3D printing of the Palmyra Arch.

On the 19th April 2016, Boris Johnson, Roger Michel and Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum of Dubai unveiled the Institute for Digital Archaeology's replica of the Triumphal Arch of Palmyra in Trafalgar Square, London, in front of the National Gallery. In his speech, Johnson said 'We are here in a spirit of defiance, defiance of the barbarians who destroyed the original.' First, watch the video below for the coverage of the event by Guardian.

|

|

|

Palmyra's Arch of Triumph replica erected in central London. Video produced by Guardian Culture. |

Although the reconstructed Arch is typically presented as a 3D printed construction, it has been actually made of marble and mechanically cut based on 3D model of the original arch. The controversial reconstruction of the Palmyra Arch sparked an interesting debate in the media and the public alike, especially in the context of post-conflict reconstruction, considering how a conflict in the Middle East was dealt by the West. Alongside, the unveiling of the reconstructed arch, Zena Kamash (2017) was running the project 'Postcard to Palmyra' in order to capture public responses to the reconstruction. After you read Kamash's paper you should write a reflection, either in the form of a diary entry or blog post, discussing the following:

- What were the (political) motives behind the 3D "printing" of the Palmyra Arch?

- What are the ethics of reproducing heritage by digital means?

- Should Palmyra and similar cultural heritage sites be rebuilt?

References

- Cronin, C. (2016). Possession is 99% of the Law: 3D Printing, Public Domain Cultural Artifacts & Copyright. USC Law Legal Studies Paper No. 16-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2731935

- Docherty, P. (2016). Nefertiti Hack – Questions regarding the 3D scan of the bust of Nefertiti. Blog post. http://www.amarna3d.com/nefertiti-hack-questions-regarding-the-3d-scan-of-the-bust-of-nefertiti/

- Harrowell, E. (2016). Looking for the Future in the Rubble of Palmyra: Destruction, Reconstruction and Identity. Geoforum 69, 81-83. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.12.002

- Huppertz et al. (2009). Nondestructive Insights into Composition of the Sculpture of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti with CT. Radiology, 251 (1): 233 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2511081175

- (2017). ‘Postcard to Palmyra’: bringing the public into debates over post-conflict reconstruction in the Middle East, World Archaeology 49:5, 608-622. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2017.1406399

- Munawar, A. N. (2017). Reconstructing Cultural Heritage in Conflict Zones: Should Palmyra be Rebuilt? EX NOVO Journal of Archaeology 2, 33-48. http://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/e4b0f492-9038-4504-bd50-bf07f95cb42b

- Nelles, J.N. and Al-Badri, N. (2016). Nefertiti Hack. http://nefertitihack.alloversky.com/

- Plets, G. (2017).Violins and Trowels for Palmyra Post-conflict Heritage Politics. Anthropology Today 33(4): 18-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12362

- The Influencers (2017). Nora Al-Badri & Jan Nikolai Nelles. https://theinfluencers.org/en/nora-al-badri-nikolai-nelles.

- Weinberg, M. (2016). 3D Scanning: A World without Copyright. Whitepaper. Shapeways. https://www.shapeways.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/white-paper-3d-scanning-world-without-copyright.pdf

Further Reading

- (2019) Whose Digital Heritage?, Third Text, 33:6, 687-707, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2019.1667629